The United States is not new to torture

As President Barack Obama grapples with accusations of torture by US agents, I suggest he consult former Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle.

I first contacted Daschle in 1975, when he was an aide to Sen James Abourezk of South Dakota, who was leading a somewhat lonely campaign against CIA abuses.

At the time, I was researching a book about the United States' role in the spread of military dictatorships throughout Latin America. Daschle arranged for me to inspect the senator's files, and I spent an evening reading accounts of US complicity in torture.

I first contacted Daschle in 1975, when he was an aide to Sen James Abourezk of South Dakota, who was leading a somewhat lonely campaign against CIA abuses.

At the time, I was researching a book about the United States' role in the spread of military dictatorships throughout Latin America. Daschle arranged for me to inspect the senator's files, and I spent an evening reading accounts of US complicity in torture.

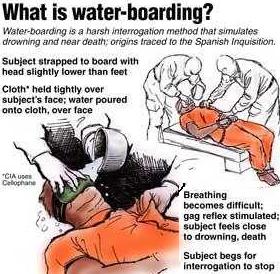

Torture Has Always Been Part of US Foreign Policy: Above Right: US Soldiers Waterboard a Vietcong Soldier For Information. Left: A US Soldier Executes a Begging Vietnamese Peasant

The stories came from Iran, Taiwan, Greece and, for the preceding 10 years, from Brazil and the rest of the continent's Southern Cone.

Despite my past reporting from South Vietnam, I had been naïve enough to be at first surprised and then appalled by the degree to which our country had helped to overthrow elected governments in Latin America.

Our interference, which went on for decades, was not limited to one political party. The meddling in Brazil began in earnest during the early 1960s under a Democratic administration. At that time, Washington's alarm over Cuba was much like the panic after the Sept 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

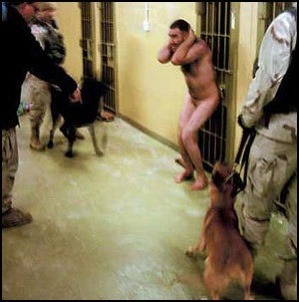

Infamous Picture of Gitmo Prisoners

President John F. Kennedy's administration was determined to prevent another communist regime in the hemisphere, and Robert Kennedy, as attorney general, was taking a strong interest in several anti-communist approaches, including the Office of Public Safety.

When OPS was launched under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, its mission sounded benign enough – to increase the professionalism of the police in Asia, Africa and, particularly, Latin America. But its genial director, Byron Engle, was a CIA agent, and his programme was part of a wider effort to identify receptive recruits among local populations.

Although Engle wanted to avoid having his unit exposed as a CIA front, in the public mind the separation quickly blurred. Dan Mitrione, for example, a police adviser murdered by Uruguay's left-wing Tupamaros for his role in torture in that country, was widely assumed to be a CIA agent.

When Brazil seemed to tilt leftward after President Joao Goulart assumed power there in 1961, the Kennedy administration grew increasingly troubled.

Robert Kennedy travelled to Brazil to tell Goulart he should dismiss two of his cabinet members, and the office of Lincoln Gordon, President Kennedy's ambassador to Brazil, became the hub for CIA efforts to destabilise Goulart's government.

On March 31, 1964, encouraged by US military attaché Vernon Walters, Brazilian Gen Humberto Castelo Branco rose up against Goulart. Rather than set off a civil war, Goulart chose exile in Montevideo.

Ambassador Gordon returned to a jubilant Washington, where he ran into Robert Kennedy, who was still grieving for his brother, assassinated the previous November. "Well, he got what was coming to him," Robert Kennedy said of Goulart. "Too bad he didn't follow the advice we gave him when we were down there."

The Brazilian people did not deserve what they got. The military cracked down harshly on labour unions, newspapers and student associations.

The newly efficient police, drawing on training provided by the United States, began routinely torturing political prisoners and even opened a torture school on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro to teach police sergeants how to inflict maximum pain without killing their victims.

One torture victim was Fernando Gabeira, a young reporter for Jornal do Brasil who was recruited by a resistance movement and later arrested for his role in the 1969 kidnapping of Charles Burke Elbrick, the US ambassador. (Elbrick was released after four days.)

John Walker Lindh "not tortured" in US captivity

John Walker Lindh "not tortured" in US captivity In custody, Gabeira later told me, he was tortured with electric shocks to his testicles; a fellow prisoner had his testicles nailed to a table. Still others were beaten bloody or waterboarded. Gabeira's captors said very little, but they sometimes boasted about having been trained in the United States.

During the first seven years after Castelo Branco's coup, the OPS trained 100,000 Brazilian police, including 600 who were brought to the United States.

Their instruction varied. Some OPS lecturers denounced torture as inhumane and ineffectual. Others conveyed a different message. Le Van An, a student from the South Vietnamese police, later described what his instructors told him: "Despite the fact that brutal interrogation is strongly criticised by moralists," they said, "its importance must not be denied if we want to have order and security in daily life."

Brazil's political prisoners never doubted that Americans were involved in the torture that proliferated in their country. On their release, they reported that they frequently had heard English-speaking men around them, foreigners who left the room while the torture took place. As the years passed, those torture victims say, the men with American accents became less careful and sometimes stayed on during interrogations.

One student dissident, Angela Camargo Seixas, described to me how she was beaten and had electric wires inserted into her private parts after her arrest.

During her interrogations, she found that her hatred was directed less toward her countrymen than toward the North Americans. She vowed never to forgive the United States for training and equipping the Brazilian police.

Flavio Tavares Freitas, a journalist and Christian nationalist, shared that sense of outrage. When he had wires jammed in his ears, between his teeth and into his anus, he saw that the small grey generator producing the shocks had on its side the red-white-and-blue shield of the USAID.

Still another student leader, Jean Marc Von der Weid, told of having his genital organ wrapped in wires and connected to a battery-operated field telephone. Von der Weid, who had been in Brazil's marine reserve, said he recognised the telephone as one supplied by the United States through its military assistance programme.

Victims often said that their one moment of hope came when a medical doctor appeared in their cell. Now surely the torment would end. Then they found that he was only there to guarantee that they could survive another round of shocks.

CIA Director Richard Helms once tried to rebut accusations against his agency by asserting that the nation must take it on faith that the CIA was made up of "honourable men." That was before Sen Frank Church's 1975 Senate hearings brought to light CIA behaviour that was deeply dishonourable.

Before Brazil restored civilian government in 1985, Abourezk had managed to shut down a Texas training base notorious for teaching subversive techniques, including the making of bombs. When OPS came under attack during another flurry of bad publicity, the CIA did not fight to save it and its funding was cut off.

Looking back, what has changed since 1975? A Brazilian truth-and-reconciliation commission was convened, and it documented 339 cases of government-sanctioned political assassination.

In 2002, a former labour leader and political prisoner, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, was elected president of Brazil. He's serving his second term.

Gabeira went home to publish a book about kidnapping the American ambassador and his own ordeal in prison.

The book became a bestseller throughout Brazil, and Gabeira was elected to the national legislature. In an election last October, he came within 1.4 percentage points of becoming mayor of Rio de Janeiro.

But in the United States, there's been a disheartening development: in 1975, US officials still felt they had to deny condoning torture. Now many of them seem to be defending torture, even boasting about it.—Dawn/LA Times-Washington Post News Service

A.J. Langguth is the author of Hidden Terrors: The Truth About US Police Operations in Latin America.

This is certainly not a photo of the United States using waterboarding torture during the Vietnam War.

This man is definitely not being tortured by the United States.

This man was not tortured by the United States, because the United States does not torture.

__._,_.___

[* Moderator�s Note - CHOTTALA is a non-profit, non-religious, non-political and non-discriminatory organization.

* Disclaimer: Any posting to the CHOTTALA are the opinion of the author. Authors of the messages to the CHOTTALA are responsible for the accuracy of their information and the conformance of their material with applicable copyright and other laws. Many people will read your post, and it will be archived for a very long time. The act of posting to the CHOTTALA indicates the subscriber's agreement to accept the adjudications of the moderator]

Your email settings: Individual Email|Traditional

Change settings via the Web (Yahoo! ID required)

Change settings via email: Switch delivery to Daily Digest | Switch to Fully Featured

Visit Your Group | Yahoo! Groups Terms of Use | Unsubscribe

Change settings via the Web (Yahoo! ID required)

Change settings via email: Switch delivery to Daily Digest | Switch to Fully Featured

Visit Your Group | Yahoo! Groups Terms of Use | Unsubscribe

__,_._,___